Recently on Search Engine Watch, we rounded up six newcomers to the search engine landscape that are worth keeping an eye on for the future.

Each new search engine takes a slightly different approach to searching the web, but there is one trait that many of the recent ones have in common: private, secure searching.

Oscobo, WhaleSlide, Gyffu and GoodGopher are just some of the non-tracking, private and secure search engines that have been launched in the last two or three years, joining more well-established engines like StartPage, DuckDuckGo, Mojeek and Privatelee.

Is this cluster of private search engines just a passing fad, or is it indicative of an increasing trend among users towards secure, private search? And if so, what does this mean for more mainstream search engines like the all-seeing Google?

I spoke to leading figures at three private search engines, both new and established – Gabriel Weinberg, founder and CEO of DuckDuckGo, Robert Beens, CEO of StartPage, and Robert Perin, co-founder and Managing Director of Oscobo – to find out why they thought more and more people could be turning to private search, and what the ramifications are for the wider industry.

Why launch a private search engine?

All three search engines whose leaders I spoke to came to the industry at very different times: StartPage was originally founded as Ixquick in 1998, and made the transition to private search in 2006; DuckDuckGo was founded in 2008; and Oscobo officially launched at the beginning of 2016.

For StartPage, the decision to become a private search engine was taken when the company noticed the sheer amounts of user data that it was accumulating and not using, and made a conscious decision to get rid of it.

For Beens, who led the initiative for StartPage to become a private search engine, it was a way for StartPage to distinguish itself in an already competitive industry, and the business case for this decision outweighed the benefits of any potential income from selling user data.

“From a business perspective, [monetizing our users’ data] makes absolutely zero sense. The only thing that sets us apart from bigger search that do monetize people’s user behavior is the fact we don’t. That’s what attracts people to us. It’s true that the revenue we make on our ads is far less than what others tend to make – so be it. It’s what makes us unique.”

Beens couldn’t have known for sure, as early as 2006, whether his gamble on a private search model was going to pay off in the long run, but he was looking for a point of distinction from Google, which was already dominant by then. “I thought that it would give us a differentiator in a difficult market at the moment. It’ll make us stand out. I’m proud of doing that.”

Beens believes that Google, along with most tech companies, has a “blind spot” when it comes to privacy – providing an opening for other search engines to compete in spite of Google’s attractive search product. His decision also gave StartPage the prestigious title of being the first search engine in the world to offer private search.

Notoriously pro-privacy search engine DuckDuckGo was also created because founder Gabriel Weinberg was looking to improve on what Google was doing, though he didn’t initially set out to create a company around his search tool. He told Forbes in an interview that he “backed into” search – “I didn’t think about it from a business perspective at the time.”

Now, however, DuckDuckGo is keen to tout the fact that it doesn’t track its users as a key selling point, along with what it believes is a cleaner, more fun design and a better overall search experience.

Robert Perin, meanwhile, was aware when he launched Oscobo in 2016 that there were already other private search options out there for people to use. Oscobo therefore decided to differentiate itself by going local – focusing initially on a UK audience, to distinguish itself from US-centric search engines like DuckDuckGo – before broadening its approach to include other countries.

A former employee at BlackBerry, Perin was inspired to develop a private search engine when he realized just how much technology was encroaching onto our everyday lives, particularly with the advent of mobile.

“Technology is creeping into our lifestyles – we carry our mobile phones around with us everywhere we go. The next step is the Internet of Things – you look at remotely-controlled heating and lighting, which can be used to analyze someone’s electricity consumption, but also to know what time they’re going home. If that data is being shared with everyone, it can be manipulated to any degree.

“Search has gone from being a relatively harmless tool to being an almighty and powerful tool. It’s the starting point for the internet. And as technology creeps into our homes and our lives, we have to hold back how much data is being handled.”

Why are people using private search?

Do people use private search purely because of concerns about data privacy? Edward Snowden’s NSA spying revelations are often pointed to as a watershed moment for people wanting to switch to private search engines. But while this is undoubtedly a significant driving factor, there is a variety of other reasons why people would opt to search privately.

DuckDuckGo’s Gabriel Weinberg points out that using a search engine which doesn’t tailor its results to the user can allow them to break out of the “filter bubble” that many users of mainstream search engines are trapped in.

“Use of a private search engine enables you to escape the “filter bubble,” where results are filtered based on what a search engine thinks it knows about you, such as your political ideologies,” he told Search Engine Watch.

“This echo chamber is extremely pernicious in a search context where you expect to receive unbiased information. Unfortunately, with other [non-private] search engines, that’s not the case.”

Robert Perin believes that tech-savvy users who know about the scope of Google’s data collection use private search to escape ‘Big Brother’, or because of ethical concerns about the amount of data being stored, even if they’re not sure how it’s being used.

Image by Patrick Barry, available via CC BY-SA 2.0

The average, non-technical person, however, is more likely to be persuaded by an argument such as dynamic pricing – in which pricing levels are adjusted based on a user’s perceived ability to pay. The prospect of unlimited choice, he says, is also a powerful one – the idea that your search results won’t be limited based on decisions that you happen to have made in the past.

“If you went to a restaurant and you were handed a menu with nothing but steaks on it, because last time you ate a steak, therefore they presume you just want a steak – you’d be kind of annoyed by that!” Perin laughs.

“And with the larger search engines, because they’re doing profiling on you, you’ll just get shown what they think you want, and also what is more beneficial to them that you click on. So it is a limited choice, in that sense.”

Is this a trend that’s growing, as evidenced by the number of new search engines that allow users to search privately?

“Absolutely,” says Robert Beens of StartPage. “There are all sorts of search engines jumping on the bandwagon, who want to get a share of that [private search] market – it’s a market that’s definitely growing.

“We’re not against it – competition is always good.”

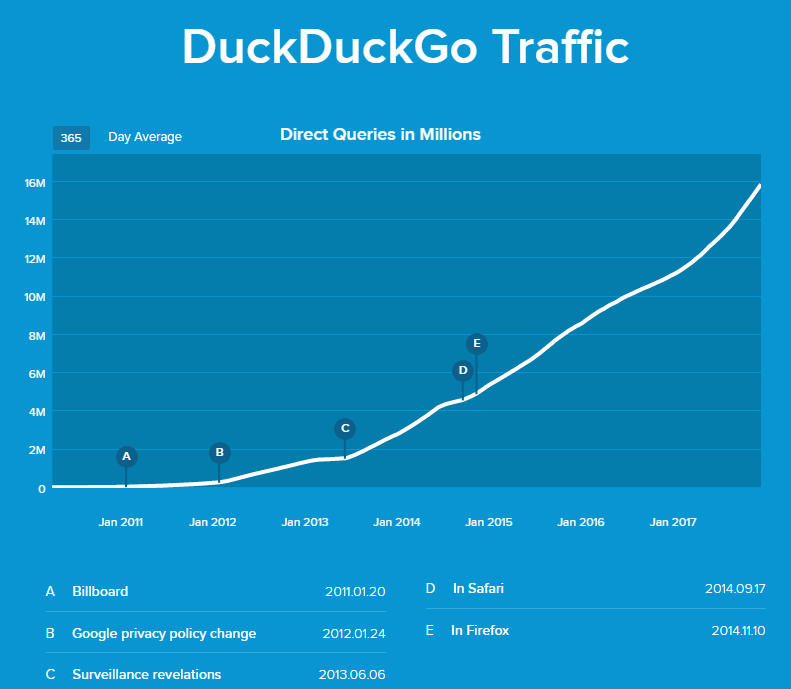

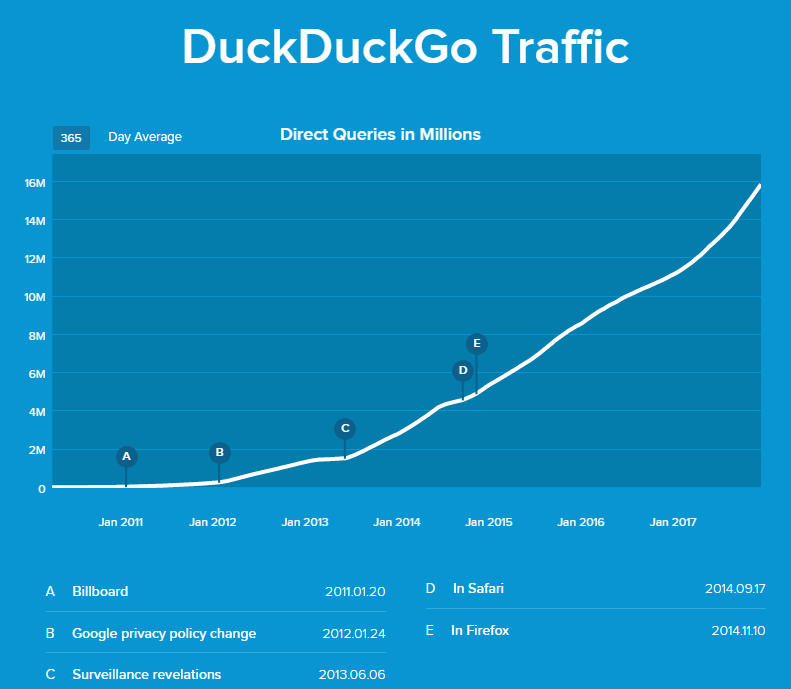

“Privacy is both mainstream and growing fast,” agrees Gabriel Weinberg, pointing to the increasing traffic numbers on DuckDuckGo as evidence of this trend in action. DuckDuckGo passed the 10 million searches per day milestone in 2015, and is closing in on the 20 million mark, with an average of around 19 million searches daily in December 2017.

“Most people still aren’t aware there is a search engine out there that doesn’t track them, though as the word continues to get out, usage of DuckDuckGo continues to increase,” says Weinberg.

“The amount of people who care about their data privacy is by no means a small number and this group is certainly not niche. 24% of US adults currently are concerned enough about their online privacy to take significant actions to try to protect it.”

DuckDuckGo’s growing traffic over time

The cost of convenience

But there’s a trade-off between the privacy and security of using private search engines and the convenience and accuracy which come from using a search engine that learns from your data and personal preferences.

Users of mainstream search engines have become accustomed to this level of uncanny, ‘mind-reading’ accuracy, and while it might be unsettling at times, they’re still unwilling to give it up even for the sake of data privacy. I asked my interviewees whether private search engines that don’t track user data can provide the same level of tailored searching as those who do.

“Most of the personalization that people want from a search engine is actually localization, like getting local weather or restaurant info,” says Gabriel Weinberg.

“We can provide those results without tracking our users because approximate location information is sent automatically with the search request, which we can use to give you relevant answers, and then immediately throw that information away without ever storing it.

“We believe you can switch to DuckDuckGo and protect your data without compromising on results.”

Oscobo’s Robert Perin admits that users might have to work a little harder to get the results they want when using a private search engine, but that ultimately, the differences aren’t huge.

“We give algorithmic results, based on just the words that you typed in,” he says.

“Searching for ‘cheap mobile phone’ doesn’t say, ‘Oh! He likes Apple – only show him the Apple ones.’ It’s going by what you’ve written. If you do want to see Apple phones, then you’ll need to type in ‘cheap iPhones’. It’s a little less intuitive, perhaps, than what we’re used to – but how much harder do you really have to work?”

“It’s a question of habits and convenience. How much of a hassle is it to have to retype ‘Hilton hotel Paris’ instead of typing ‘H-i-l’ and having the search completed for you? Is that a massive, massive benefit that’s worth selling your identity for?

“And also, what’s the cost? I think when people realize what the cost of convenience is, then they change.”

Robert Beens of StartPage agrees that once people become aware of the extent of the data tracking that takes place online, they are likely to want to change their habits.

“If you give me five minutes to talk to people, I can convince them to use a private search engine.

“But the personal data market exists below the surface – no-one knows about it, and it takes a fairly technical level of understanding to know what’s going on. So it takes education and awareness of the facts behind data tracking, and then people can make a conscious choice to use one or the other.”

What does this mean for Google and SEO?

If there is indeed a steadily snowballing trend towards the use of private search engines, is this going to impact on mainstream, user-tracking search engines like Google and Bing further down the line? And what about SEO? Do SEOs need to start worrying about optimizing for private search engines?

Well, no. While the approach that DuckDuckGo, StartPage, Oscobo and others take to data privacy is different to Google and Bing, the search technology that underpins them is often the same as those used by mainstream search engines. Robert Perin refers to Oscobo as a “Bing/Yahoo feed”, while StartPage gets its results from Google.

DuckDuckGo draws its search results, particularly Instant Answers, from a wider range of sources including Wikipedia and DuckDuckBot (its crawler); but it also has an agreement in place with Bing, Yahoo and Yandex in which these search engines provide results without any user data being exchanged.

Private search engines see this as an opportunity to provide users with the best of both worlds – the accuracy of more advanced search technology, with the anonymity and security of private searching.

As for repercussions for Google, Perin is skeptical about whether a trend towards private search will make a difference to Google, which is unlikely to do anything meaningful to give up the reams of user data on which it relies for so much of its revenue. (According to Investopedia, about 90% of Google’s entire income stems from advertising).

Source: Statista

Source: Statista

“Ultimately, I think they’ll do everything they can to keep as much data as they can, because that’s where the value is.”

Perin emphasizes that Oscobo isn’t looking to disrupt mainstream search engines with what it does. “Our aim wouldn’t be to shake [Google] up; it’s to give people an alternative.”

Robert Beens echoes this, stating, “The choice is free. If people want an alternative, we want to be there with the best product that we can have.”