Going over to the duck side: a week using DuckDuckGo

I’ve heard about DuckDuckGo a few times over the years, mostly as a name uttered in hushed whispers behind closed doors – “You don’t have to use Google. There is another way.”

I’ve heard about DuckDuckGo a few times over the years, mostly as a name uttered in hushed whispers behind closed doors – “You don’t have to use Google. There is another way.”

I’ve heard about DuckDuckGo a few times over the years, mostly as a name uttered in hushed whispers behind closed doors – “You don’t have to use Google. There is another way.”

As far as I knew, it was a small, scrappy start-up that had nevertheless managed to make its mark in the world of search, dominated as it is by the vast and all-knowing Google.

Frustration with Google might be at a high at the moment with tax-dodging, increasing dominance of search (and now the mobile web) and removing ads on the right hand side at the expense of organic search results.

Therefore I was intrigued by the comments from DuckDuckGo fans on Jason Tabeling’s article on whether you should be paying more attention to DuckDuckGo, urging people to switch to DuckDuckGo and discover the ‘real internet’. How would searches from such a small engine stack up against Google’s, in everyday situations? Would using DuckDuckGo be an exercise in frustration, or a revelation?

I decided to test the waters, using it as my ‘go-to’ search engine every day for a week.

The first thing I did was to install the app on my phone. DuckDuckGo has native apps for both iOS and Android, and compared to most apps which oblige you to sign away your first-born child before installing, its requirements are refreshingly simple.

Of course, this is DuckDuckGo’s main ethos: it “doesn’t track you”, as the desktop version of the search engine likes to remind you, and protecting your privacy is front and centre of its concerns. The mobile app has a straightforward and flexible set of privacy settings, including an option to enable Tor (this requires installing a proxy app like Orbot).

Compare this with Google’s rather lacklustre ‘Accounts & privacy’ settings:

The desktop version also boasts a range of privacy options, including the option to prevent sharing your search with sites you click on (a shame for anyone who tracks analytics, but great for privacy-focused users) and the ability to save your settings anonymously to the cloud.

DuckDuckGo lets you customise it in a whole variety of other ways, including changing the theme and modifying different parts of the appearance, which I had fun playing around with. You can even opt to turn off ads, and DDG helps you to make up for this by giving you ways you can spread the word instead.

I couldn’t help thinking that Google tries to customise your experience of using its search engine by gathering vast amounts of data and trying to intuit what you want, whereas DuckDuckGo simply lets you choose.

So now that I was all set up, how did it deliver with search? The first test came when I wanted to look up more information about a story a friend had mentioned on Facebook, about a baby dolphin dying after it was pulled from the ocean and passed around for selfies.

I couldn’t quite believe it was true, but a quick Duck (DuckDuckGo’s equivalent of the verb ‘Google’, though I’m not sure whether this one is going to catch on) confirmed that it was:

DuckDuckGo aims to win users over by being helpful without being intrusive. So it won’t amass vast stores of data in order to be unerringly, creepily accurate in predicting what you’re after, but it will, say, present you with a carousel of recent news stories on the topic you just searched.

One such useful feature is Instant Answers, which highlights information designed to give you a quick answer to your search query at the top of the page, similar to Google’s Knowledge Graph or Bing’s Snapshot Search and Autocomplete.

It’s a great idea in theory but falls down a little in its coverage of topics. A search for “Who is Thomas Jefferson”, for example, summons a little Wikipedia bio and a huge range of ‘related topics’ at the side, ranging from “burials at Monticello” to “American deists”; whereas a search for “what is a leap year” just returns a regular results page.

DuckDuckGo is an open source project, so Instant Answers, like many of its features, is community contributed: if you spot an area that doesn’t have an Instant Answer associated with it, you can get involved and add it yourself.

This has its advantages and disadvantages; on one hand, it gives users a practical way to improve the search engine in ways that are relevant to them. On the other, it requires Instant Answers to be added and refined one by one, which takes time and can be frustrating for users who just want to access the information they need in that moment, with the minimum of effort.

I didn’t get to truly put many of DuckDuckGo’s features through their paces with just a week of using the search engine, but it gave me a sense of how most of them could be used.

I enjoyed the way that search results scroll vertically into infinity instead of requiring you to click onto the next page to see more. It feels effortless and gives the impression of diving deeper into a topic, instead of the stigma which tends to surround ‘the second page of results’ on Google.

Then there are ‘!bangs’, a much-touted DuckDuckGo feature, which mystified me when I first saw the little exclamation point next to the search box in DuckDuckGo’s mobile app.

By typing an exclamation mark and a keyword – usually the website name – followed by your search term, you can search directly within a site from DuckDuckGo. So searching for “!ebay teapot” will take you straight to the search results for “teapot” on eBay.

It’s a neat little time-saver which has benefits for DuckDuckGo as well, as it collects a commission from eBay and Amazon for anything that you purchase from those sites after visiting them through DuckDuckGo.

!bangs work with many more websites than just those two, of course; the list of !bangs is currently over 7,800 sites long, and you can add any site that isn’t already covered by filling in a form. It’s unclear how long these take to process, though – after discovering that Search Engine Watch wasn’t on the list, I submitted it as a !bang, but at the time of writing it isn’t yet up and running.

Where DuckDuckGo falls down

When it comes to search engines that aren’t Google, I definitely consider DuckDuckGo to be ahead of the flock. With its unwavering emphasis on privacy, fine-tuned customisation and strong community, it has something genuinely different to offer users instead of just playing catch-up to Google with its features.

But it’s still a search engine that isn’t Google, and in spite of DuckDuckGo’s best efforts to offer a “smarter search”, it’s not able to match Google for sheer accuracy and intuition. A number of times as I researched articles throughout the week, I resorted to Googling something rather than waste any more time trying different keywords on DuckDuckGo.

Part of the problem is likely to be that as a lifelong Google user (except for a brief fling with Ask Jeeves in the very early days), I’ve moulded my search habits to fit with what I know works on Google, and I expect Google’s uncanny levels of accuracy in return.

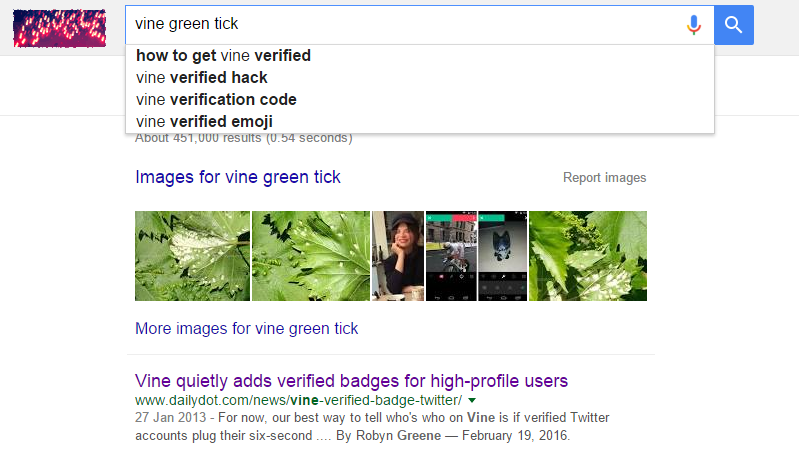

The best example of this came up while I was researching a piece on what to consider before jumping on a new social media bandwagon for ClickZ. I couldn’t remember what the account verification icons on Vine, the equivalent of Twitter’s ‘blue tick’, were called. So I searched for “Vine green tick” on DuckDuckGo.

After several frustrated attempts and pages of nonsense results about grape vine pests and the comicbook superhero ‘The Tick’, I searched Google for “Vine green tick”. It immediately returned this as the top result:

Google: you have to admit, it gets results.

Whether Google used its semantic search techniques to know that I had been spending a lot of time on social networks and reading articles about social media to give the correct context to my search, or whether it was able to use its vast stores of data on what previous users had searched to intuit the right result, it was able to find in one search what DuckDuckGo couldn’t manage in four or five.

The question is, am I indignant enough about Google’s knowledge of my browsing habits (and everyone else’s that feed its all-knowing algorithms) to trade the convenience of instantly finding what I’m after for that extra measure of privacy online?

My assessment of DuckDuckGo after spending a week in the pond is that it’s a search engine for the long term. To get the most out of using it, you have to make a conscious change in your online habits, rather than just expecting to switch one search engine for another and get the same results.

Many of its features require you to actively contribute to the search engine to help make it better; you have to put in what you expect to get out. And you have to sacrifice some of what Google has trained you to expect from a search engine in order to ease yourself out of the filter bubble.

Does this bother you enough to change your search engine?

Does this bother you enough to change your search engine?

Photo by Patrick Barry, some rights reserved.

A lot of people are already bothered enough by what Google (and other huge, omnipresent online entities) has been doing to make the switch. As for me, while I’m not sure whether I’m ready to make the break with Google just yet, I’m listening.

I do think that DuckDuckGo is the only search engine offering something substantially different enough to challenge Google. It’s not backed by a huge corporation, but it doesn’t need to be. Actually, that would defeat the object of it.

Unlike most major search engines whose main offering is, let’s face it, ‘basically Google but slightly worse’, DuckDuckGo offers users genuine privacy, control, customisation, a certain amount of hipster street cred and an opportunity for endless duck puns.

And if you’re still not convinced, take a look at our mega list of alternative search engines to find your favourite.

If you enjoyed this article, check out our piece on the recent popularity of privacy-focused search engines: What’s behind the trend towards private search engines?