All eyes are on whether Google is feeling lucky, after a third attempt at launching a social product.

The Google+ Project launched on Tuesday to a small cache of users who are currently test driving the project in what a Google spokesperson told us is a ‘limited field test’.

A select number of press correspondents have access to accounts but, as was the case when GMail launched, the rollout is so exclusive that the rest of us will have to wait for an invite. In the case of GMail, the exclusivity of the service created word of mouth buzz and also demand for the service among Google’s power user set.

By contrast, Google Buzz, Google’s first foray into social products was a feature activated in GMAil accounts without users permission, co-opted people’s email contacts as ‘friends’ and subsequently faced a storm of controversy over privacy. Needless to say, Google Buzz failed to get any attention but negative press.

From the launch strategy alone, The Google+ Project has already put its best foot forward. However, from conversations with numerous industry professionals and esteemed network theory experts, our verdict is that Google+ is getting some things right, but has one fundamental hurdle to overcome.

In short, Google Plus needs to make sure it does not get fixated on sharing as simply a matter of privacy and instead focus user attention on sharing with purpose.

The Google+ Launch

Whilst the launch of this latest social product is characteristic of Google’s best strategies, there are elements of this particular rollout that bear mentioning as they are indicative of a wider and longer term strategy and more importantly, indicative of it’s ultimate vision of what a Google approach to social sharing is.

In conversation with a PR spokesperson, Google told SEW that Google+ represents “Google’s approach to sharing”. This phrase is key, as Gmail was introduced as Google’s Approach to Email – and represents a return to core values – something we expected to see with the appointment of Larry Page as the new CEO.

Among changes we expected to see in tow with the successor of Eric Schmidt was ‘social’ layers being added to Google products, rather than the search giant trying to create its own ‘online social network’ in the sense that we know it now. That is to say, Google categorically is not trying to create a new Facebook or Twitter, but instead is simply trying to leverage the potential benefits of user profiles in its products.

To that end, what we’re seeing with Google+ is that it’s been named a project, rather than a network and the ‘+’ brand suffix seems to indicate that they intend to create an eco-system of social applications that sit on top of its core products.

The Facebook Approach to Sharing

In conversation with network theory experts, I found out that the thinking goes that in the world of online sharing, people tend to ‘overshare’ on Facebook and the dreaded reply-all button on an email often leads people to screw up among their peers.

The reason for this is that, ironically, online social networks like Facebook are nothing like our real life social networks.

In fact, there is something fundamentally wrong about the design of Facebook. It’s almost the opposite of real life. In “real life” we don’t live our lives as if we are a single monolithic public identity that does not differentiate our behavior between groups of friends. In fact, on a daily basis we are constantly adapting our behavior to different ‘social circles’.

This is common sense to everyone, but it’s worth elucidating that the average healthy and sane person presents different personas in respect to their different social groups. Each group sees a different aspect of you and knows different things about you, so much so, that all of us introject a subconscious permission system from the social group – so that we decide what we want to share, depending on who we talk to. There is a kind of second order reasoning at play too which is calculating all the subgroups one is interconnected with – for example, we deliberately might not invite a particular person to a party because we don’t want their friend to come along.

As human beings we are constantly subconsciously managing our connections between all these different groups and subgroups and the reality, is that networks are just as much about restricting the flow of information as they are about enabling it.

Since social networks first started appearing online, with Orkut, Friendster and now Facebook, all the subtleties of networking in real life have been ignored in favor of a new model maximized for sharing. Facebook has created an alternative mode of networking which creates an ambient awareness of others’ via an asynchronous presence. One of the most interesting design features of Facebook is the fact that we can share with no expectation of a response from any specific person. In that sense, Facebook itself has become like a social circle that comes with its own set of rules.

Contrary to what the average user thinks, namely “who needs another Twitter or Facebook?”, industry experts do believe that there is still a lot of room in the online world for innovative social products. Email has always been good for one to one communication, whilst Facebook is good for one to many, but (despite privacy/friends list settings) no one has mastered one to few communication on Facebook.

Google’s Approach to Sharing

So, given that Facebook users can be roughly divided between chronic over-sharers (evidenced by blogs like Failbook and the extremely gun-shy, the premise of Google’s strategy to solve this problem is fundamentally sound. If they can master few to many communication then what Google stands to gain is the entire eco-system of content that currently isn’t being shared by the gun-shy averse to over-exposure. By killing the ability to overshare, Google could tease out the confidence of the, relatively speaking, more introverted power user – and leverage a tonne of ‘new’ social data.

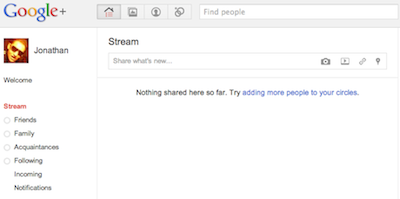

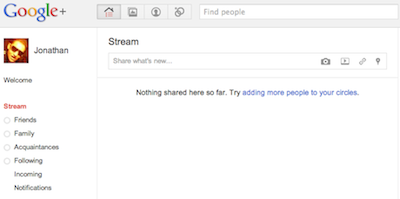

One of the first, most obvious aspects of Google+ is that it puts segmentation at the core of the user experience. As soon as you get into Google+ you are prompted to put your friends into ‘circles’ that they suggest, or create your own. It is no different to Facebook friend lists, except that much of the functionality of Google+ does not surface until you have done that basic activity. Once you have, you can browse through different streams being shared within the social circles you have defined.

Out of the box, Google+ seems to have got this right – the entire project is geared towards limited and selective sharing.

However, this is where Google+ gets into hot water. There is a lot that can start to go wrong at this point. To get it right, Google+ relies on users being able to fully articulate their social circles, which people actually cannot do. We’re simply not wired to be fully cognizant of what social circles we actually move in or who they are made up of. Beyond friends and family, every other social group we belong to is induced by a common purpose.

We only have to consider the difficulty of specifying meta data or semantic classifications to see that we quickly get into a never ending layers of meaning and context.

Even the most avid Google fan can dive zealously into categorizing their contacts, only to find that the most useful circle is the ‘everyone’ bucket. Friends, family, followers and acquaintances are not particularly useful categories to do anything I can’t do on other networks, except perhaps share photos.

Personally speaking, it has already been a challenge to decide whether I differentiate professional friendships from personal friendships, or work on the basis that they are all ultimately friends. Even colleagues from work count as friends, so do i want to limit their visibility of my profile to just work stuff? No, because friendship and work, at least in my case, overlaps. Then comes the focus of friends from different parts of the world – should i create a circle for every country or city to differentiate these friendships? It serves little practical purpose unless I am sharing in different languages.

In the end, I had created half a dozen circles that were poorly differentiated with a few members, who often occupied at least two other circles.

Google+ relies on users manually creating these classifications and if they don’t (simply because people will not do things they are forced to do), they can’t generate any value from the sharing platform. Put another way, if users do not define circles, there is nothing to do on Google+ — absolutely nothing.

If Facebook can’t get users to use friends lists effectively, why should it be any different on Google+?

The Double Bind

The most obvious way for Google to overcome this hurdle is to auto-suggest groupings. You only have to look at the Google Ad Preferences associated with your account to see that they have a pretty good idea about who you are. Equally, aligning interests among your friends could be a way of auto-generating your social circles. Google could suggest those associations to you so that all one has to do is click accept.However, according to experts in this area, automatically suggesting associations between people is harder than one might expect and throws up a lot of false positives. Erroneous groups could emerge based on your interactions. For example, a viral video about a sneezing panda could generate a lot of buzz among your contacts, but it does not warrant creating a group of sneezing panda fans.

Even if Google+ can effectively suggest circles, they risk drawing the ire of users who feel their privacy might be threatened. Yet, if Google+ does not start auto suggesting social circles it’s unlikely to have staying power with a mainstream audience.

It seems ironic that the almighty power of Google is barely brought to bear on The Google+ Project. Maybe this explains their tentative rollout?

They have to find out how users respond to +circles and if ‘protecting privacy’ is enough of an incentive to organize your contacts.

+Denouement

There is actually no inherent need to solve the problem of over-sharing simply for the sake of it. Whilst we have all seen the repercussions of over-sharing play out, say particularly in political life, the benefits of living publicly often outweigh the benefits of living privately.

The benefits of living publicly on the internet have their own obscure benefits. The web has made social class more permeable and YouTube ‘sensations’ such as Rebecca Black, and others before her, have seen stratospheric rises for careers. The broadcast mechanism afforded by YouTube, Twitter and Facebook is the purpose of using those networks in and of itself. That chance of discovery is worth the risk of over-sharing.

Arguably, against the background of broadcast networks like Youtube, Facebook and Twitter, the protections Google+ makes for privacy to some degree sacrifice the use case for the mainstream user simply because we’ve all become accustomed to the idea that online social products are about maximizing reach.

Yet, if we let go of the broadcast purpose, and return to the way in which we actually network in real-life, Google+ starts to look more like a set of collaborative workflow tools that can be put to any purpose. Putting aside any notion of similarity to Facebook, the major differentiator between Google+ is its focus on live sharing – Hangouts enables live video between 10 people and Huddle enables group chat when you are on the move.

In this way, the Google+ platform brings with it the promise of being in step with real-life rather than the promise of fame. To get the best out of it, we will have to step beyond the notion of ‘engagement’ much touted by social media gurus and solely focus on ‘purpose’. If Google wants to gain ground in social it is going to have to drop the dialectics of privacy, and refrain from asking its users “what are you upto now?” or “what is on your mind?” and squarely focus user attention on the question, “what do you want to achieve?”.

Google+ needs to elucidate its own purpose fast – and privacy is not the purpose.

Rather than asking me to organize my contacts into friends, family, followers and acquaintances, the Google+ UI needs to bite the bullet and ask me what I am up for in life. If Google can get me to focus on my real-life goals, I would gladly organize those contacts into social circles that can help me achieve them.